It belongs in a museum —

Paramount released 4K Blu-Ray collection of first 4 films to mark the occasion.

Jennifer Ouellette

–

Indiana Jones (Harrison Ford) relishes the challenge of stealing a Peruvian fertility idol.

LucasfilmAlfred Molina made his film debut as the treacherous guide, Satipo.

LucasfilmSatipo gets his comeuppance.

LucasfilmIndiana outruns a giant boulder. The fiberglass, plaster, and wood boulder was controlled by a concealed steel rod in the rubber rock wall.

LucasfilmRene Belloq (Paul Freeman) prefers to let Indy do the hard work and then steal precious artifacts from him.

LucasfilmAn apple for teacher.

LucasfilmUS Army intelligence agents have a proposition for Indiana.

LucasfilmIndy and Marcus Brody (Denholm Elliott) celebrate their new mission: to find the Ark of the Covenant.

LucasfilmMarion Ravenwood (Karen Allen) can drink most men under the table.

Lucasfilm“Indiana Jones. I always knew some day you’d come walking back through my door.”

LucasfilmSadistic Gestapo agent Arnold Ernst Toht (Ronald Lacey) also wants the head piece to the Staff of Ra.

Lucasfilm“Whiskey….”

LucasfilmCareful, that medallion is hot!

LucasfilmJohn Rhys-Davies played Sallah, an Egyptian excavator who is Indy’s ally in Cairo.

LucasfilmMarion makes a monkey friend.

LucasfilmThe monkey is a spy! Vic Tablian played the Monkey Man.

LucasfilmMarion’s makeshift weapon is no match for that knife.

LucasfilmIndiana faces a Cairo swordsman (Terry Richards).

LucasfilmTime constraints forced Steven Spielberg to nix an elaborate whip vs. sword fight scene. Instead, Indy just shoots the swordsman.

LucasfilmThat treacherous monkey reveals Marion’s hiding place.

LucasfilmIndiana drowning his sorrows in the wake of Marion’s presumed death.

LucasfilmMarion is alive! Captured by the Nazis.

Lucasfilm“Heil Hitler.”

Lucasfilm

I still remember the thrill of watching Raiders of the Lost Ark for the first time in the summer of 1981. I spilled my popcorn at the very first jump scare: our hero, Indiana Jones, triggered a booby trap while tracking a Peruvian fertility idol, and a skewered, decaying skeleton popped into the frame. From then on, it was a nonstop ride of thrills, chills, and more than a few spills, with enough humor, romance, and supernatural mysticism thrown in to capture anyone’s imagination. Snakes! Spiders! A Nazi monkey spy! Plus plenty of explosions and a gross-out melting face! Next to the first Star Wars movie, it was the best movie I had yet seen in my relatively young life.

I wasn’t alone in my enthusiasm, despite a tepid trailer that captured none of the action/adventure flick’s enduring magic. Critics (mostly) raved, and audiences flocked to theaters to see Raiders again and again for several months after its release on June 12, 1981. It was the top-grossing film of that year and didn’t leave theaters until the following March, ultimately grossing $354 million globally. Raiders was nominated for multiple Oscars, winning five (for film editing, art direction, sound, sound editing, and visual effects). The Library of Congress selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry, and it is widely considered to be one of the greatest movies of all time. Even director Steven Spielberg has said he considers it the most perfect film in the franchise.

(Major spoilers below because it’s been 40 years, and who even are you if you haven’t seen this movie yet?)

George Lucas had wanted to make an homage to the serial adventure films of his youth since 1973 and came up with the idea of a globe-trotting adventurous archaeologist named Indiana Smith. (Indiana was the name of Lucas’ Alaskan Malamute, which became a throwaway quip at the end of 1989’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade: “We named the dog Indiana!”) He got distracted by other films, including Star Wars, released in 1977. That same year, Lucas was vacationing in Hawaii with Spielberg and pitched his Indiana Smith idea. Spielberg convinced him to change the last name to Jones and eventually came on board as director.

With screenwriter Lawrence Kasdan, the two men held a marathon brainstorming session the following January in Los Angeles, coming up with an outline and several key set pieces. It was Kasdan’s job to weave all those elements together into a coherent, compelling narrative; he found inspiration in classic films like Red River, Seven Samurai, and The Magnificent Seven. Several Hollywood studios rejected the project, balking at the proposed $20 million budget (a mere pittance by today’s standards). But Paramount finally agreed, with producer Frank Marshall joining the team to make sure Spielberg stuck to his budget.

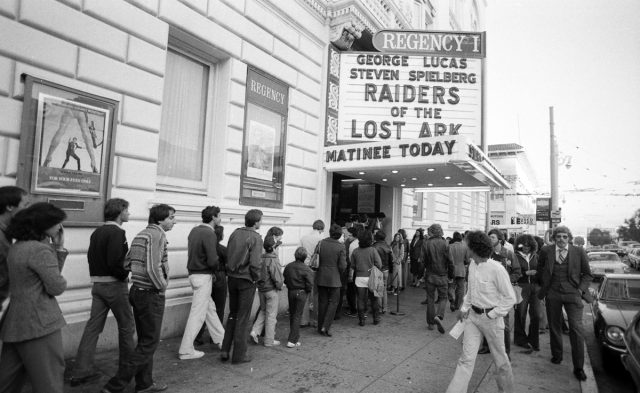

Enlarge / Crowds in line to see Raiders of the Lost Ark, June 25, 1981.

Steve Ringman/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images

Lucas had originally conceived Indy as something of a womanizer and Kung Fu expert, with Spielberg suggesting he could be a gambler or an alcoholic—just to make him fallible and vulnerable and to bring some lighter comic touches to the character. Only the womanizing element really stuck. Among those considered for the role were Chevy Chase, Bill Murray, Nick Nolte, Peter Coyote, Jack Nicholson, and Tom Selleck. Of course, Harrison Ford—already a star thanks to his portrayal of Han Solo in Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back (1980)—was in hindsight the perfect choice, bringing the same mix of tough cynicism masking a heart of gold, bravado, and self-deprecating humor that made Han Solo such a fan favorite.

Casting relative newcomer Karen Allen—best known at the time for a supporting role in 1978’s Animal House—as Indy’s love interest, Marion Ravenwood, was another inspired choice. She beat out Amy Irving, Debra Winger, and Sean Young, among other contenders for the role. Spielberg, Lucas, and Marshall were looking for an actress who could hold her own against the swashbuckling Indiana Jones, bucking the typical damsel in distress stereotype. Although Marion does her share of yelling, “Indeeeee!” when she’s in a tight spot, she’s hardly a passive shrinking violet: she’s equal parts feisty, smart, funny, and vulnerable. Allen brought all those qualities and more to the role—”I was never really a girly-girl,” she recently told the Hollywood Reporter—which is why she remains the franchise’s best and most popular love interest for the archaeologist.

Allen’s natural adventurous spirit came in handy for some of the more difficult scenes, such as being trapped with Indy in the snake-infested Well of Souls. Unlike the fictional archaeologist’s famous aversion to snakes, after the first few days, Allen took the serpents in stride, particularly since there was usually plexiglass between the actors and the cobras. There was also a nurse armed with antivenom and an ambulance on call—just in case. A few folks on set did get bitten by pythons, Allen recalled, which are not poisonous, although “it is a nasty bite.” Even more dangerous was the fight scene in the burning Nepalese bar: Allen and Ford did their own stunts for that scene, and yes, the fire was real.

Enlarge / Harrison Ford and Steven Spielberg on the set of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

Much has been written over the years about the eventful 73 days of shooting. Because of the tight schedule, Spielberg couldn’t indulge in very many takes—usually only three or four, although he later said this constraint kept the film from being pretentious. The cast and crew endured temperatures of 130° F in Tunisia, and Ford and several crew members came down with amoebic dysentery. The opening sequence set in Peru was actually filmed in Hawaii, and while they found the perfect cave location, it was also near a mosquito breeding ground, with everyone suffering multiple bites. And the tarantulas covering the guide Satipo (Alfred Molina) were all male and thus not aggressive. When they just wouldn’t move, the crew placed a female spider on his chest to encourage them.

During another scene, a fly visibly landed on Paul Freeman’s face as his character, rival archaeologist Rene Belloq, calls Indy’s bluff to blow up the ark. Freeman didn’t even miss a beat; he just continued with his lines. But the fly didn’t really crawl into his mouth; the scene was edited in post-production to make it appear that way, and the sound team added some extra buzzing to call more attention to the fly. And it took 50 takes to get the monkey to perform its scene-stealing Nazi salute, coaxed by a grape hanging over its head. For all the headaches, however, Lucas felt it was a relatively smooth shoot, in large part because the studio didn’t interfere.

If Raiders shows its age at all (apart from the delightfully dated special effects), it’s in the broad ethnic stereotypes, from the one-note Nazi caricatures (like Ronald Lacey’s sadistic Gestapo agent) to the Egyptian dig workers at Tanis and street beggars in Cairo. More troubling by today’s #MeToo standards is the romantic history between Indy and Marion—the cause of his falling-out with her father, Abner. “I was a child!” Marion protests when confronting him about ruining her life. “You knew what you were doing,” he replies.

Allen has said Marion was 16 and Indy was 26 at the time. But a 2008 oral history of the film reports that Lucas suggested Marion was 11; Spielberg protested, saying “She had better be older.” (Ya think?) Allen recently defended the age difference, insisting that the exact nature of the relationship was deliberately vague, and the two may have only “kissed a few times”—which would have been a big deal for a starry-eyed teenager of that era.

Indiana in the map room, as he discovers the location of the Well of Souls, resting place of the ark.

Lucasfilm“Why did it have to be snakes?”

LucasfilmMarion’s escape attempt is foiled.

LucasfilmRemoving the ark from the Well of Souls.

LucasfilmAlas, the Nazis have captured Sallah.

LucasfilmJones is trapped in the Well of Souls.

Lucasfilm“Why Dr. Jones, whatever are you doing in such a nasty place?”

LucasfilmMarion is tossed into the well with him. But of course, they’re going to escape…

LucasfilmThe climactic moment in the (largely improvised) fight between Indy and a brawling Nazi (Pat Roach).

LucasfilmMarion mans the machine gun.

Indy gives chase to the truck convoy transporting the ark.

Ford did many of his own stunts, but for this one, Spielberg used a stuntman.

“It’s not the years, it’s the mileage.”

Captain Simon Katanga (George Harris) negotiates with Colonel Dietrich (Wolf Kahler) for Marion.

LucasfilmA fly visibly landed on Freeman’s face while shooting this scene. Freeman didn’t miss a beat.

The opening of the ark initially proves disappointing.

The Nazis dared to laugh, and the ark decides to take vengeance.

A Lucasfilm receptionist in a long white robe was suspended in front of a blue screen for this shot.

A skeletal model based on the receptionist’s face completed the transformation.

Dietrich’s head shrivels, courtesy of a mold lined with air-filled bladders.

The infamous melting face involved a sculpted model with layers of different colors of gelatin over a heat-resistant stone skull.

“Don’t look at it , Marion.”

“Top. Men.”

LucasfilmThe ark is buried once again, this time in a cavernous government warehouse.

As for real-world archaeologists, let’s just say they have a longstanding love/hate relationship with Raiders. On the one hand, it makes archaeology look cool as hell; there was a subsequent increase in students wanting to major in archaeology after the film’s release. On the other, it’s a vision of archaeology that is vastly different from how the field has evolved since the 1930s, as archaeologist Kristina Killgrove recently noted in an article for Smithsonian magazine. She and her colleagues vented their various frustrations with Indy’s disregard for ethical guidelines, the lack of racial and gender diversity, and the inaccurate depiction of archaeologists as treasure hunters.

Despite all of that, University of California, Berkeley, archaeologist Bill White ruefully admits that Indiana Jones made him want to become an archaeologist in the first place. “These movies are an escape for many of us, including archaeologists,” he told Killgrove. “I want non-archaeologists to know that’s not really how archaeology is, but I don’t want them to lose the value of these movies as fantasy, action, and adventure.”

The Sound of Raiders of The Lost Ark with Ben Burtt and John Roesch, one of the original Foley artists for the film.

Given Raiders‘ box office success, a sequel was soon forthcoming: 1984’s Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. While it, too, was a box office success, that film had none of the magic of the original. The humor is forced, Kate Capshaw’s constant screeching grates on the nerves, and one of Indy’s allies is a young Chinese boy known only as Short Round, if we’re talking about outdated ethnic stereotypes. Also: chilled monkey brains for dessert, anyone? (Because poking fun at weird ethnic food is such a laff riot.) I still find the film practically unwatchable decades later. Fortunately, The Last Crusade was a welcome return to form, with Sean Connery lighting up the screen alongside Ford as Indy’s academic egghead father.

Alas, the franchise stumbled yet again with 2008’s Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, although we did get Karen Allen’s return as Marion, Cate Blanchett as a deliciously evil villain, and the useful film trope “nuking the fridge” as an updated term for “jumping the shark” (inspired by a particularly implausible scene). All the key franchise elements were there, they just never gelled, and it ended up mostly feeling tired and lifeless. The film still grossed nearly $800 million worldwide, even though critical reviews were mixed.

A fifth Indiana Jones film (as yet untitled) just started filming earlier this month, with James Mangold (Logan) replacing Spielberg as director. We seem to alternate between good films and bad ones, so maybe that pattern will hold and we’ll get the magic again with this new outing. Ford, now 78, is returning as Indy, so he will not be passing the bullwhip to Shia LaBeouf, who played Mutt, his son with Marion, in Crystal Skull. Phoebe Waller-Bridge and Mads Mikkelsen have been cast in undisclosed roles, and both Allen and Rhys-Davies have expressed interest in returning as Marion and Sallah, respectively. And of course, John Williams will be composing the score; bringing in anyone else would be sacrilege.

In the meantime, to mark the film’s 40th anniversary, Paramount has released a 4K Blu-Ray collection of the first four Indiana Jones films for your home viewing pleasure, and all are available for streaming. But if you’re fully vaccinated and live near one of the handful of theaters screening Raiders of the Lost Ark this month, it’s well worth catching it on the big screen—if only for nostalgia’s sake.

Listing image by LucasFilm