Be gone, before we taunt you a second time! —

The Tlingit built the Sapling Fort in 1804 to repel a Russian naval attack.

Kiona N. Smith

–

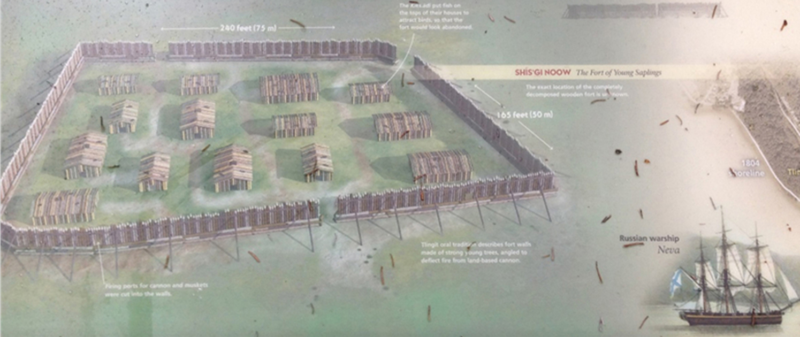

Enlarge / This interpretive sign at the presumed “fort clearing” includes a reconstruction of what the fort probably looked like in 1804.

In 1804, Tlingit warriors sheltered behind the walls of a wooden fort on a peninsula in southeastern Alaska, preparing to repel a Russian amphibious assault. An archaeological survey near the modern community of Sitka recently revealed the hidden outline of the now-legendary fort, whose exact location had been lost to history since shortly after the battle.

The coolest battle you never heard of

The Tlingit had already sent Russia packing once, in 1802, after three years of mounting tensions over the Russian-American Trading Company (a venture akin to the better-known British East India Company), which had a presence on what is now called Baranof Island. Because the Tlingit elders—especially a shaman named Stoonook—suspected that the Russian troops would soon be back in greater numbers, they organized construction of a fort at the mouth of the Kaasdaheen River to help defend the area against assault from the sea.

By 1804, the Tlingit had procured firearms, shot, gunpowder, and even cannons from American and British traders. They had also built a trapezoid-shaped palisade, 75 meters long and 30 meters wide, out of young spruce logs, which sheltered more than a dozen log buildings. The Tlingit dubbed it Shis’gi Noow—the Sapling Fort.

The Tlingit had built fortifications before; in 1799, the Russians set up their trading post practically in the shadow of a hilltop fortification called Noow Tlein, or Big Fort. But this time, Stoonook and his people had engineered their fort specifically to counter the threat of naval guns.

“This fort is different than other Tlingit forts, and may have been adapted in response to an expected naval attack,” Cornell University archaeologist Thomas Urban told Ars. The log palisade was meant to be sturdy enough to repel cannon projectiles, and the strange trapezoidal shape was “probably a function of the anticipated directions of naval cannon fire, but not known for sure,” according to Urban.

Lead vs. wood

When the Russian sloop-of-war (a small warship) Neva arrived in September 1804, the ship’s guns couldn’t even put a dent in the sturdy wooden palisade. (In fairness to the Russians, a sloop-of-war doesn’t pack much of a punch, relatively speaking.) “It was constructed of wood, so thick and strong, that the shot from my guns could not penetrate it at the short distance of a cable’s length (about 185 meters),” wrote Lt. Cmdr. Yuri Feodorovich Lisyansky, Neva’s commanding officer.

The Russians sent 150 men ashore, mostly Aleut warriors fighting on behalf of their Russian allies. But the landing force found itself facing a hail of gunfire and a savvy two-pronged attack by the Tlingit. While half the Tlingit force emerged from the fort to engage the enemy head-on, the other half waited in the woods to attack the Russians’ and Aleuts’ exposed flank. The would-be invaders beat a disorganized retreat back to Neva under the dubious cover of the sloop’s guns.

For the modern Tlingit, “the fort is a cultural symbol of resistance to colonization, and the location is considered sacred by many community members,” Urban told Ars. But for the last 200 years, only its approximate location has been known. A recent geophysical survey of the peninsula revealed the ghostly outline of the fort, long hidden beneath the ground.

This interpretive sign at the presumed “fort clearing” includes a reconstruction of what the fort probably looked like in 1804.

Russian Lt. Cmdr. Yuri Lisyanski drew this sketch of the Sapling Fort just before burning it down in 1804.

Lisyanski 1804Electromagnetic induction (EM) and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) both detected an “anomaly” at the same location, and its shape bears a striking resemblance to an 1804 sketch of the fort.

Urban et al. 2021

Historical fort lost and found

Urban and his colleagues used ground-penetrating radar and a technique called electromagnetic induction, which measures differences in how the soil conducts an electric current, to search a 17-hectare swath of the Alaskan coast for traces of the past. Both surveys revealed the buried foundations of walls forming the shape of a trapezoid roughly 75 meters long and 30 meters wide, exactly like the fort described in Tlingit oral history and Russian writings. It could only be the Sapling Fort.

“The location and protection of the fort site and broader battlefield has long been of significant interest to the Sheetka Kwaan Tlingit, especially those of the Kiks.adi Clan,” wrote Urban and his colleagues. The Kiks.adi clan built and defended the Sapling Fort under the leadership of war chief Ḵ’alyaan.

Archaeologists had been trying to pinpoint the exact site of the Sapling Fort since 1910, when then-President William Taft declared the site a national monument (now Sitka National Historic Park). Several digs found compelling hints about the fort’s location, like cannonballs and possible fragments of buried walls. With the available evidence, the National Park Service could only point to a cleared area on the otherwise forested peninsula. Meanwhile, archaeologists and historians kept suggesting alternative sites for the fort.

The recent geophysical survey seems to have settled the question. It lines up well with the results of a 1958 survey, which claimed to have excavated parts of the southern and western walls of the Sapling Fort. Electromagnetic induction also found some buried metal debris in the northwest corner of the fort, near where an earlier survey had found cannonballs.

A symbol of resistance

But why was the fort lost for 200 years? The Russians burned it to the ground a few days after the Tlingit repelled their amphibious assault.

The Tlingit had stashed their supply of gunpowder across Sitka Sound, perhaps to prevent it from accidentally blowing up the fort if a stray cannonball landed in the wrong place. Early in the siege, Russian cannon sank the Tlingit canoe making its way back to the Sapling Fort with a load of powder. The resulting explosion cut off the Tlingit powder supply and killed a respected elder and several high-ranking young members of the Kiks.adi clan.

Despite the setback, the Tlingit held off the Russian and Aleut advance for several more days. The delaying action bought the clan’s civilians time to flee to safer (and less contested) ground. In what is now called the Sitka Kiks.ádi Survival March, the women and children hiked north across Baranof Island, then rowed canoes across a strait to Chichagof Island (both islands are now part of the modern city of Sitka, Alaska).

Meanwhile, the fort’s defenders even managed to pull off a stealthy, organized retreat under cover of darkness in order to provide a rearguard for the fleeing Tlingit civilians. The next morning, several days after the first landing, Cmdr. Lisyansky and his Aleut allies walked into the empty fort. They sketched it in detail before burning it to the ground.

“Perhaps the battle could have gone in a different direction [if the Tlingit hadn’t run out of gunpowder],” Urban told Ars. “But ultimately Russia had more resources with which to wage war, so a different outcome for the battle might not have necessarily meant a different long-term outcome.”

Today

But the people of the Kiks.adi clan had pulled off no small feat; they had bloodied the invaders, held them off for several days, and gotten the clan’s people to safety—all without the help of other clans whose alliance they had spent two years requesting. The Battle of Sitka, as it’s now known, is a proud piece of history for the modern Tlingit.

“Tribal members have maintained ongoing involvement and interest in archaeological work within the park, and representatives of the Sitka Tribe of Alaska have responded favorably to the new findings,” wrote Urban and his colleagues.

Antiquity, 2021 DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2020.241 (About DOIs).