Kids —Despite the strong voting results, many advisers had concerns and caveats.

A panel of independent medical experts advising the Food and Drug Administration voted 17 to 0 (with one abstention) this afternoon in favor of authorizing the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for use in children ages 5 to 11 years old.

The vote is a key step toward the first pediatric COVID-19 vaccine in the US. Next, the FDA will need to sign off on the recommendation from the advisory panel—the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC)—and issue an emergency use authorization for the 5-to-11 age group. That FDA authorization is expected within days. Once that occurs, the federal government will begin shipping pediatric doses of the vaccine to states for distribution at clinics, pharmacies, and pediatricians’ offices.

But before doses can go into any little arms, a panel of independent experts for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will also need to weigh in. That panel—the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—is scheduled to meet November 2 and 3. If ACIP votes in favor of recommending use of the vaccine in children ages 5 to 11, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky will need to sign off on the committee’s recommendation. That would likely happen quickly, and after that, vaccinations can begin.

Many parents and caretakers are anxiously awaiting the vaccine’s availability. With kids back in schools for in-person learning and fall and winter holidays looming, there’s clear eagerness to have a protective vaccine for school-aged children. However, there’s also plenty of concern and anxiety among some about offering vaccines to those kids, who have lower risks than adults of developing severe COVID-19. One of the biggest concerns is vaccine-associated myocarditis (inflammation of the heart), which has shown up as a significant risk for older teens, particularly males ages 16 and 17. This all makes weighing the risks and benefits of vaccines in the 5-to-11 group particularly tricky.

While today’s favorable vote was widely expected, VRBPAC’s all-day meeting Tuesday was no cakewalk. Committee members carefully combed through efficacy, safety, and modeling data prior to their vote. And there was plenty of disagreement and hesitation. Just prior to the vote, some committee members floated the idea of only authorizing the vaccine for high-risk children. In the end, the committee determined that the efficacy and safety data was enough to issue an authorization, though concerns lingered about possible mandates.

Vaccine data

Prior to today’s meeting, Pfizer had released data indicating that smaller doses of its COVID-19 vaccine could safely and robustly protect children. Initial data suggested that two shots of just a third of the adult dose—10 micrograms instead of the adult dose of 30 micrograms—produced comparable antibody levels in children ages 5 to 11 as those seen in vaccinated teens and young adults. The smaller doses in younger children also seemed to have similar side effects as seen in older groups, such as fatigue, headache, fever, and chills.

Additionally, a trial run by Pfizer and BioNTech involving about 2,250 children suggested that the pediatric formulation was about 91 percent effective at preventing symptomatic disease. The trial ran through the delta wave, suggesting that the vaccine is effective against the highly transmissible variant.

Last week, the FDA released its internal review of the data showing that the vaccine’s benefits of thwarting the pandemic coronavirus and preventing COVID-19 cases would “clearly outweigh” the risks of myocarditis.

In opening remarks at today’s meeting, Peter Marks, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, unambiguously stated the case in favor of authorizing the vaccine.

“Far from being spared from this harm of COVID-19 in the 5 to 11 year old age range, there have been over 1.9 million infections, over 8,300 hospitalizations, about a third of which required intensive care unit stays, and over 2,500 cases of multisystem inflammatory disorder from COVID-19,” Dr. Marks said. “And there have also been close to 100 deaths, making it one of the top 10 causes of death in this age range during this time. In addition, infections have caused many school closures and disrupted the education and socialization of children.”

COVID risks

Further data presented by the CDC showed that children 5 to 11 are making up a larger proportion of COVID-19 cases. The youngsters accounted for 10.6 percent of all cases as of earlier this month, despite being only 8.7 percent of the population. And that’s likely a significant undercount. Antibody screening suggests that around 42 percent of children in this age range have been infected.

Though 5- to 11-year-old children have lower rates of hospitalization than other pediatric groups, there were 8,300 hospitalizations in the age group. Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native children had the highest rates of hospitalizations in the cohort. In one data set, 68 percent of hospitalized 5- to 11-year-old children had at least one underlying medical condition, such as asthma or obesity. But 32 percent had no underlying conditions.

Myocarditis

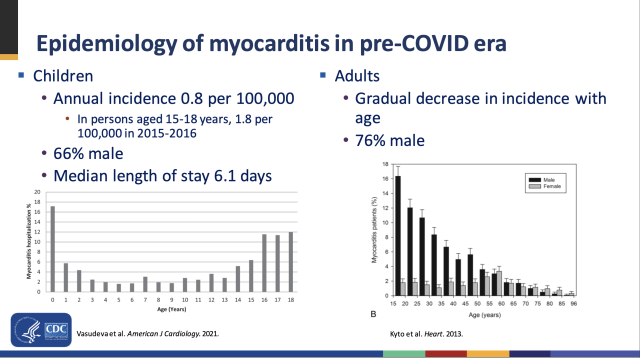

The committee also heard detailed data on the risk of myocarditis, which is most significant in young males. But the data we have so far suggests the risk may peak in males ages 16 to 17, similar to what’s seen in “classic” myocarditis cases from the pre-pandemic era. For instance, according to the latest data, there were around 70 cases of myocarditis for every 1 million doses of vaccine given to males ages 16 to 17. But the rates dropped to about 40 cases per 1 million doses in males 12 to 15 and 37 cases per 1 million doses in males 18 to 24.

This mirrors what has been seen before with myocarditis. Case rates overall are higher in males, and the risk is bimodal with age. Infants less than 1 year old and teens 16 to 18 have the highest rates of hospitalization for myocarditis. Between infancy and adolescence, the risk is low, and it declines gradually after the adolescent peak. Why this trend exists is unclear, but medical experts suspect that the infant peak in myocarditis is linked to congenital problems and the adolescent peak is related to testosterone levels—which also helps explain why it’s mainly seen in males.

The similarities between the pattern emerging from vaccine-related myocarditis and “classic” myocarditis make medical experts hopeful that 5- to 11-year-olds will have much lower risks of myocarditis than are seen in the 12-to-15 and 16-to-17 age groups. Another positive point: nearly all cases of vaccine-related myocarditis continue to be generally mild, and most kids recover fully.

But without any data on the specific 5-to-11 age group, it’s impossible to determine the kids’ actual risk. Even in the highest-risk group to date—male teens 16 to 17—the rates of myocarditis are too small to assess without millions of people getting vaccinated.

Modeling

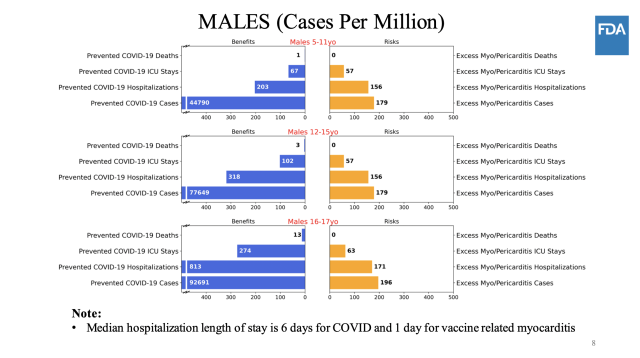

In the absence of satisfying data, the CDC turned to thorough risk/benefit modeling to explore all the possible outcomes. The agency modeled the risks and benefits of vaccinating 5- to 11-year-olds in various scenarios, starting with COVID-19 case rates at levels seen in early September, assuming vaccine efficacy was 70 percent against cases and 80 percent against hospitalizations, and assuming the rates of myocarditis were the same as those seen in kids ages 12 to 15 (scenario 1). Researchers then tweaked the model outcomes if COVID-19 case rates were higher or lower (scenarios 2 and 3, respectively), if vaccine efficacy was higher (scenario 4), if COVID-19 death rates were higher (scenario 5), and if rates of myocarditis cases were lower (scenario 6).

Enlarge / Scenario 1.

In all of the scenarios—except when COVID-19 case rates were very low (scenario 3)—the benefits of vaccinating kids ages 5 to 11 outweighed the risks of myocarditis. In scenario 3, the model predicted hospitalizations and ICU stays from vaccine-related myocarditis would outnumber the COVID-19 hospitalizations and ICU stays that vaccines would prevent. Still, as several experts noted in the discussion periods, the myocarditis rates used in all but scenario 6 are likely significant overestimates.

Scenario 2: high COVID. Scenario 3: low COVID. CDC

Scenario 4: high vaccine efficacy. CDC

Scenario 5: high COVID death rate. CDC

Scenario 6: lower myocarditis risk. CDC