Price: £54.99

Developer: Kojima Productions

Publisher: Sony

Platforms: PC, PS4

Version Reviewed: PC

Hideo Kojima has developed a reputation as one of gaming’s greatest storytellers. Death Stranding proves this reputation is overblown. Slow, excessive and self-indulgent, Death Stranding’s narrative labours under long-winded exposition, tedious dialogue, and themes about as subtle as a herd of rampaging elephants. The ideas are interesting, but the delivery is dreadful, which is particularly unfortunate given Death Stranding is a game about delivering the goods.

Yet for every flaw in its storytelling, Death Stranding also proves that as game designers, Kojima and his team are worthy of their reputation. That same tendency toward indulgence that makes the story so frustrating also results in deep and layered systems that are compelling to grapple with and produce wonderful emergent moments. It shares much in common with the studio’s previous work on Metal Gear Solid V. Yet whereas that game was focussed on stealth, tactics, and violence, Death Stranding is about traversal, exploration, and rebuilding.

Death Stranding puts you in the role of Sam Porter Bridges, a one-man courier service who spends his days trekking across America making deliveries. But America isn’t the America we know and are increasingly perturbed by with every passing day. An apocalyptic event known “the Death Stranding” has turned the United States into Iceland, a rugged and barren landscape without a Wendy’s in sight. The event also connected Earth to another existence inhabited by strange, oily ghosts known as BTs. If a person is killed by one of these monsters, it triggers a “voidout” – a massive, city-flattening explosion that leaves behind enormous craters in the landscape.

Luckily for Sam, he’s a “Repatriate”, able to essentially survive these voidouts and return from the dead. This makes him the ideal candidate for a new project cooked up by what’s left of America’s government. Known as the UCA, this organisation plans to reconnect the country’s remaining cities via a system called the Chiral network – sort-of a holographic Internet. After spending far too long deliberating, Sam inevitably agrees to help, and sets off on an epic journey across fractured America, delivering what the cities need to rebuild their infrastructure and reconnect the country under the UCA’s banner.

Now, playing a fifty-ish-hour open-world game in which you’re basically a sci-fi postman may sound like the most boring thing on Earth. But Death Stranding simply acknowledges the fact that most open-world games treat you like the world’s greatest skivvy anyway. The quest might be “Go here, kill this” or “Go there, steal that,” but the principles are fundamentally the same. Death Stranding recognises there are only so many ways to dress up a fetch quest, so instead, it focusses on making the bit between those quests, the travel, as interesting as possible.

For the first ten hours or so, Death Stranding is basically a hiking simulator. The game’s hyper-detailed photogrammetric capture of Iceland’s landscape offers more than stunning vistas and a unique virtual world to explore. It creates a topography of harsh relief, all steep hills and slopes, crags and ravines. Navigating this rugged environment involves much more than simply pressing forward. Sam’s movement is influenced by momentum and balance. Move over rough terrain too quickly, and Sam’s cargo will begin to list, eventually causing him to stumble.

Pressing both mouse buttons simultaneously will see him try to regain his balance, and it’s important to try to do this. If you fall over, not only will you take damage, your cargo will too. This can incur score penalties upon delivery, and if the cargo is destroyed will require you to backtrack to acquire a new load. Hence, it’s wise to plan your routes as best you can, examining the map for potentially tricky obstacles and figuring out paths around them.

From this foundation, Death Stranding layers in an impressive array of sub-ideas and mechanics that result in one of the deepest exploration systems of any open-world game. It starts with a few basic tools, such as extendable ladders that can be used to climb steep rock-faces and cross rivers, alongside climbing ropes that you can use to abseil down mountainsides. Over time, you’ll unlock the ability to build bridges, equipment generators, and even roads, alongside vehicles such as delivery bikes and trucks, robots that make automated deliveries, exoskeletons that let you move faster or carry more cargo, and weird floating carts that let you trail a load behind you like a human freight train.

Forging new pathways over inhospitable terrain is one of the most satisfying elements of Death Stranding. What makes it even more fun is those pathways are not just for you. Death Stranding’s world exists in a hybrid single and multiplayer state, similar to Dark Souls, but much more involved. You never see or interact with other players, but some of their structures will appear in your world, as will yours in some of theirs. This stuff is carefully layered in over time, and consequently the world gradually evolves around you as you play. It also encourages collaboration. You can help deliver other player’s packages, come together to build new roads and other advanced structures. Doing this earns you extra “Likes”, Death Stranding social-media-inspired XP that upgrades your general cargo-bearing skill, and unlocks extra abilities.

This gradually trickle of upgrades and world changes lends an immense amount gratification to completing Death Stranding’s deliveries. But they’re also cleverly balanced out by other hazards in the game world. The introduction of vehicles might appear to render the hiking element of Death Stranding redundant, for example. But since new areas are not connected to the Chiral network, they lack the right infrastructure for proper vehicular use, and so it’s usually best to initially explore these places on foot.

Then there’s arguably Death Stranding’s strangest concept, the phenomenon of timefall. It doesn’t rain water in Death Stranding world. It rains time. Any object or organism these “raindrops” touch will be advanced along their own natural timeline. It makes skin age, plants grow and wither, and cargo and structures rust. It’s a fantastic way of making weather a more active component in the game, lending a sense of urgency whenever timefall commences, and also giving the world a natural sense of decay, a reason for you to build new equipment, structures and vehicles over time.

Timefall often heralds the arrival of BTs – oily, spectral creatures that hover menacingly in the air. Largely invisible, you need to use a special scanner to pinpoint their approximate location, moving slowly and quietly to evade them when they appear. BT encounters are wonderfully tense, as you’re forced to slow down while knowing every second spent in the timefall eats away at your cargo containers, threatening to ruin your load. And if you’re caught by a BT – well, I won’t spoil what happens – but it’s way more involved and spectacular than I expected, as well as being legitimately horrifying.

On the opposite side of the enemy spectrum are MULEs, crazed bandits who live for hoarding cargo. Whereas BT encounters are about moving slow and carefully, to deal with MULEs you have to either run or fight. Some of my most exhilarating moments in Death Stranding have been MULE chases, leaping over crevasses with a back full of cargo, dodging the stun-spears they toss at you which electrify the surrounding ground.

From a play perspective, I found Death Stranding to be highly engrossing, a rich and smartly-designed open-world experience. That said, there were aspects of it that tested my patience. Menus are cluttered and fiddly to use. It’ll often take you five to ten minutes to set up for a new delivery, while completing orders involves navigating several screens dedicating to tallying up all the “Likes” you earned on that order, usually accompanied by a small speech from whoever you gave the order to telling you what a great job you did. Just shut up and let me get back out there, Random Warehouse Guy #121. I don’t care how much those spare parts mean to you.

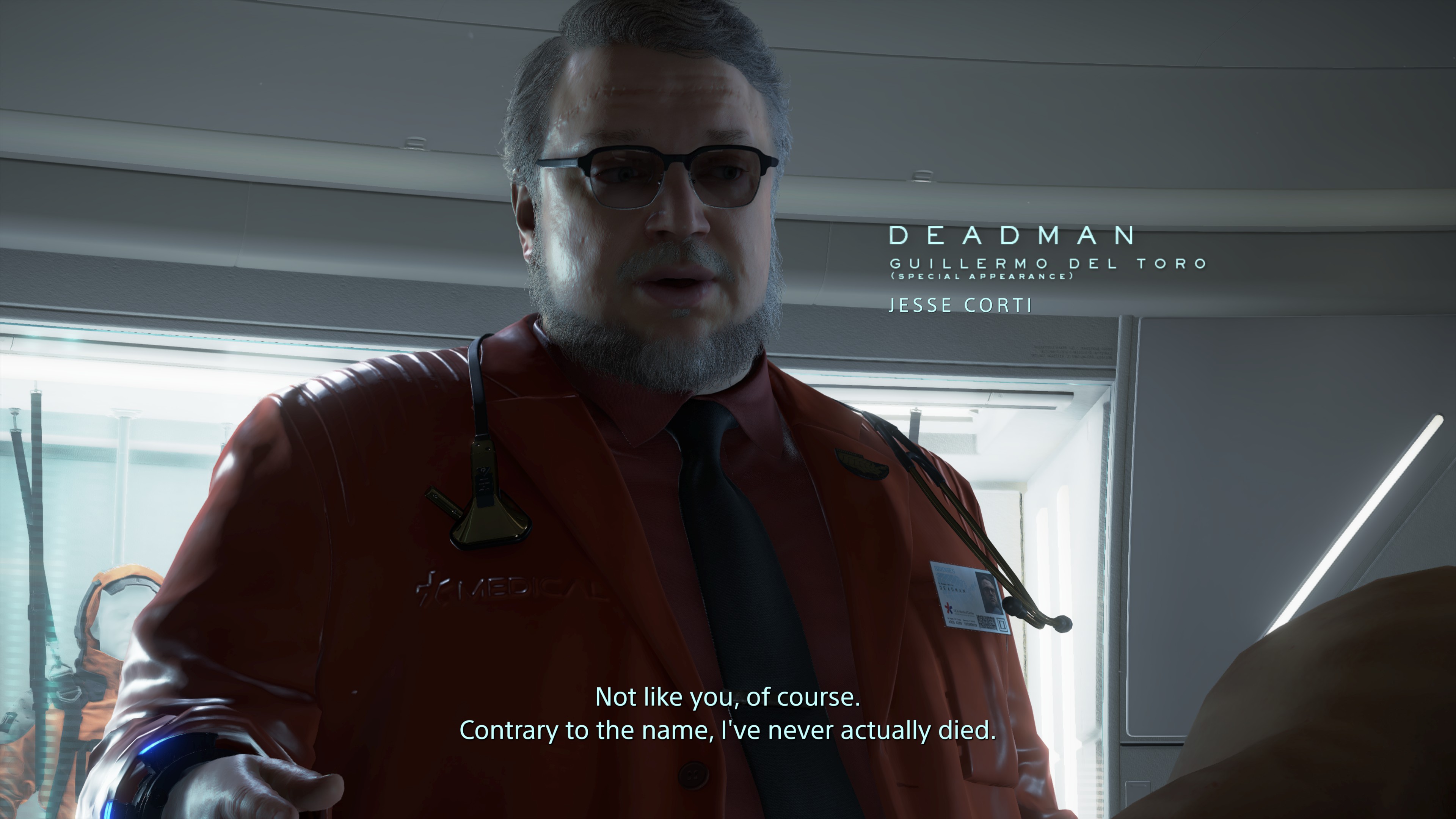

The circuitous nature of Death Stranding is an issue throughout the design, but it’s most evident in the story. In terms of ideas and general imagery, Death Stranding’s tale is interesting, and you can’t fault the acting talent on show. Norman Reedus convincingly grunts and murmurs his way through the world as Sam, and I enjoyed Kojima casually dropping in not just A-list actors but big-name directors like Guillermo del Toro and Nicolas Winding Refn (who both have a ball playing their respective characters). Léa Seydoux in particular does a fantastic job wringing emotion out of some truly awful lines as Fragile, Death Stranding’s equivalent of Metal Gear Solid’s Sniper Wolf.

No matter how good the performances are, they can’t alter the fact that the script is at best passable and at worst appalling. Many cutscenes drag on endlessly, especially toward the end when they start to come in blocks. Characters also don’t pop as they should. Themes and metaphors are played far too heavily, and it seems like everyone needs to repeat anything they say three times to make sure that you understand it.

Indeed, there’s no getting around it, Death Stranding is too long. After twenty hours with it, I checked to see how far along I was, and discovered to my dismay I’d just finished chapter 3 of 15. It turned out that was the longest chapter, mercifully, but you could still shave at least twenty hours off Death Stranding and be left a tighter, more engaging experience.

Still, for all its narrative faults, the game itself is well worth playing. Grappling with Death Stranding’s treacherous terrain highlights that good open-world games are not so much about the where or the why, but the how. How are you going to that location? How are you going to collect the object you need? How are you going to carry 200 kilos worth of cargo over a mountaintop? In the end, it isn’t Kojima’s story that lingers in the mind, but the stories the game’s systems enable you to create. That, fundamentally, is what gaming is all about, and despite the script’s best efforts, Death Stranding understands this implicitly.