Price: £13.49

Developer: Consumer Softproducts

Publisher: Consumer Softproducts

Platform: PC

I’ve tied myself into critical knots thinking about Cruelty Squad, a hybrid FPS/immersive sim which looks like a playable migraine and sounds like capitalism’s death-rattle. It’s an oblique and surreal experience designed specifically to push buttons in you that you didn’t know existed to be pushed, and it’s undoubtedly one of the most fascinating games to release this year. Yet while I appreciated much of what Cruelty Squad does, I can’t say that I really enjoyed playing it. But then, maybe that’s the point? Argh.

The game puts you in the role of a depressed assassin who is recruited by the eponymous Cruelty Squad to perform extreme, high-level corporate liquidations in the service of the shady conglomerate that owns the Squad. It basically rides the same line as Cyberpunk 2077, presenting players with a hyper-capitalist dystopia where a handful of elites play corporate Game of Thrones while everyone else struggles just to survive. But it approaches the topic from the complete opposite direction.

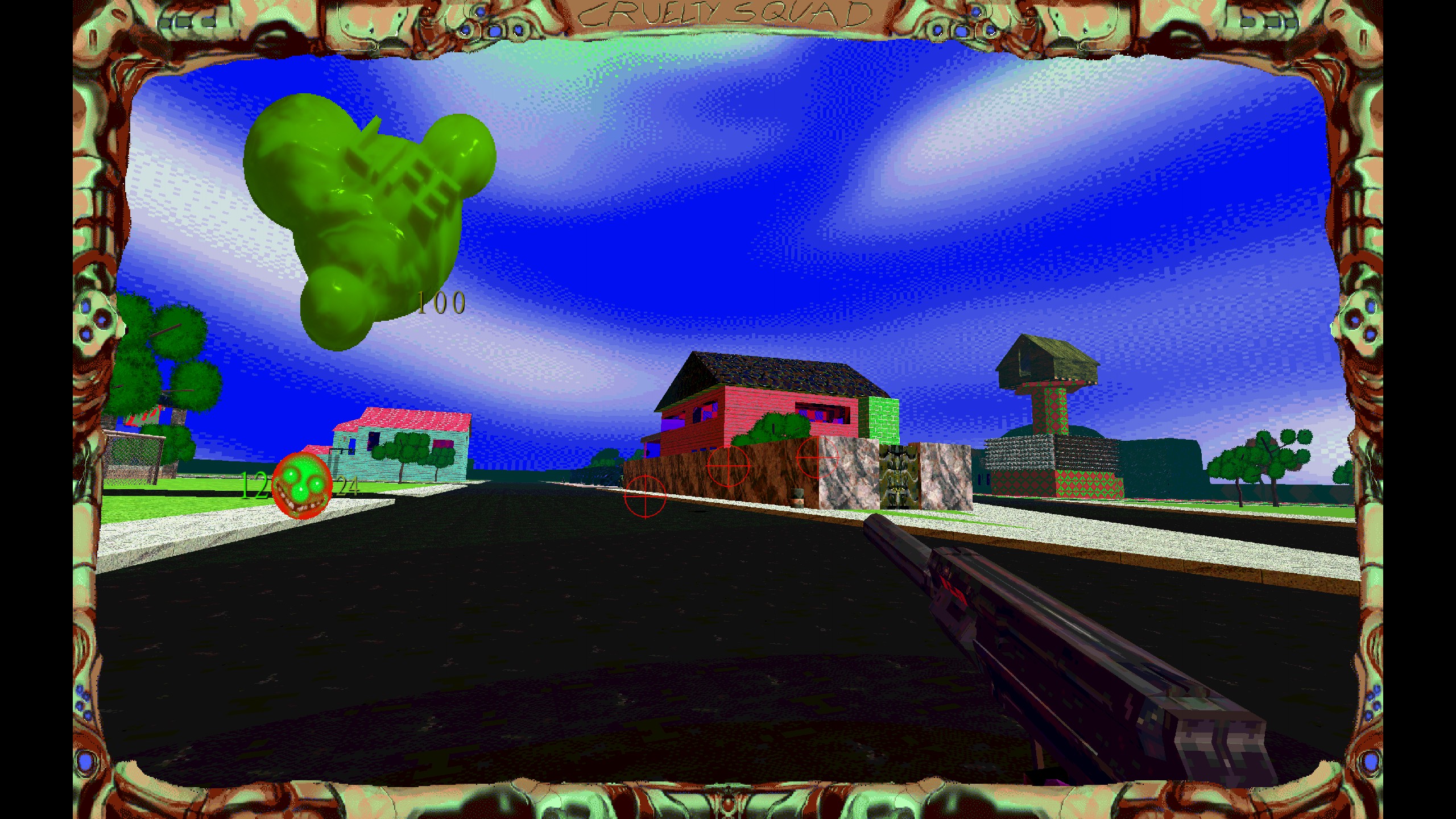

This is most evident in the visual style, which isn’t so much lo-fi as anti-fi, meticulously designed to be a lurid and aesthetically repulsive as possible. The whole game is painted in toxic greens and fleshy pinks and browns, looking like it would squidge if you touched it (before giving you an infection). Clipart is splashed liberally throughout menus and environments, while characters are polygonal lumps roughly bashed into shape, each wearing a horrifying rictus grin stretched across its face.

The intent here is not simply to deliberately look “bad”. Rather, it’s to actively make you feel uncomfortable, to deny you both the dopamine-drip of modern graphics rendering and the comfort of nostalgia offered by other retro-styled games. In this Cruelty Squad is profoundly effective. It is constantly a disturbing experience, frequently veering into straight-up horror.

Yet there is beauty within Cruelty Squad, which is found at a geometric level rather than a textural one. Each of Cruelty’s Squad’s 13 main missions is large and open-ended, giving you one or several targets to eliminate and leaving the approach largely up to you. An early example tasks you with assassinating three targets in a wealthy suburb of Cruelty Squad’s city, where each house is more like its own separate compound with its own wall and private security. You can try to infiltrate these compounds directly, but you can also crawl along the fringes of the map, exploring other building for sniping vantage points or other equipment that might aid you in your mission.

Like IO’s Hitman, levels can be completed in a matter of minutes, but only if you have the right knowledge and equipment. Exploration and repetition are key elements in progression. Unlike Hitman, how you progress is highly oblique and not necessarily bound to logical rules. For example, at the game’s outset, every death incurs a penalty of $500 for rebuilding your body, which is a lot considering your payment per hit is around $1000. Die enough times, however, and you’re selected for a special program where your body regenerates itself for free. This also gives you the ability to regain slivers of health by eating corpses.

Peeling back Cruelty Squad’s idiosyncratic layers is probably where I enjoyed it most. The game features around 20 weapons, which can be added into your inventory by picking them up in a level and bringing them back with you. There is also a wide array of body augmentations available, ranging from simple speed and endurance upgrades to weird stuff like the ability to use your own entrails as a grappling hook. Many of these upgrades are prohibitively expensive, requiring you to master the game’s volatile stock market, selling fish or bodily organs retrieved from the enemies you kill on the black market for profit, and gaming the system to earn huge amounts of cash.

All of this I found intriguing. My issue with Cruelty Squad is that I didn’t particularly enjoy it as a shooter. Enemies are of the old-school hitscan variety, making a beeline for you the moment they’re alerted to your presence and obliterating your health-bar within a few shots. Die, and you’re catapulted back to the start of the level. There’s no real failure spectrum in Cruelty Squad. You can’t really evade alerted enemies, and while you can regain lost health, those gains are often so marginal that you might as well not bother.

Fighting effectively in Cruelty Squad, therefore, is all about having the quickest trigger finger, peeking around corners for a quick headshot and then waiting for other enemies to come pouring into your sights. While this makes combat tense, I didn’t find it particularly interesting, reminiscent of the painfully unforgiving early Rainbow Six games. Also, while I’m perfectly fine with Cruelty Squad’s visuals, I couldn’t get on with how it feels. Weapons are limp and unsatisfying, which also goes for most other interactions.

As I said at the outset, this may well be the point. Perhaps a game about assassinating people for corporate gain shouldn’t feel good. It’s certainly consistent with Cruelty Squad’s general themes and unfolding plot. One of my favourite parts of Cruelty Squad are the written briefings you get before each mission, which are the only explanation you get as to why you’re doing what you’re doing. In one level, you’re tasked with assassinating the CEO of an aeronautics company because they’re doing their job too well, and their efforts to make a manned mission to Mercury safer are at odds with the conglomerates plan for a “sacrificial” mission.

Cruelty Squad is bold, radical and unique, and it certainly gave me a lot to think about. But is it fun? I’m not sure, nor am I certain that’s it’s supposed to be. It’s a fascinating experiment in artistic game design, but it’s also one that’s hard to generally recommend. Nonetheless, I’m extremely glad that it exists, and if you like ambitious level design and your tolerance for jank is high, you’ll probably get something out of it.