Early Catholic mission records obtained by CBC News, along with the oral history of elders from Cowessess First Nation who attended Marieval residential school in Saskatchewan, help shed some light on the 751 unmarked graves found in the community cemetery last month after a ground-penetrating radar survey.

WARNING: This story contains distressing details.

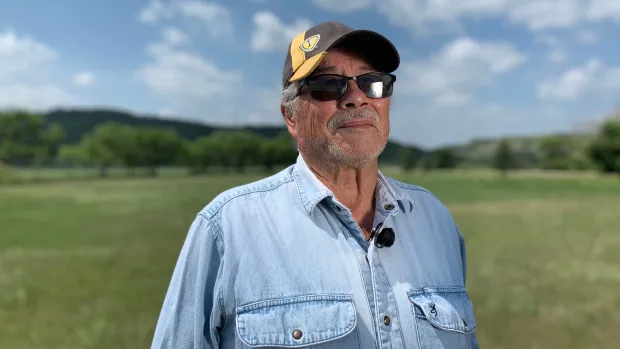

Lloyd Lerat still remembers the day in the early 1960s when workers came to remove headstones from a section of the cemetery in Cowessess First Nation, Sask., that is now covered with tiny flags marking spots left by a ground-penetrating radar survey that the nation says found evidence of 751 unmarked graves.

A student at Marieval Indian Residential School at the time, Lerat, 72, said he and other children heard a hubbub of activity coming from the cemetery near the school, located about 164 km east of Regina. They saw workers and a truck removing headstones and wooden crosses.

“We came out, and there were all kind of activity going on there,” said Lerat.

“We knew something was happening so we would watch, but don’t get caught, you couldn’t go running. You had to just take a look and say, OK, something’s happening and to see them being, I don’t know, gathered somehow, either pushed out of the way and picked up.”

Lerat, who returned to work at the school in the 1970s, rising to become administrator of the residence in the 1980s, said he doesn’t know where the workers put the headstones and wooden crosses.

Several stories have surfaced in the community about what happened to the grave markers, and they all agree on one thing: a priest ordered their removal in the early 1960s. But no one story explains why, and officials from the Catholic Church, which ran the school until the late 1960s, have not been able to confirm the account or explain why either.

A similar uncertainty shrouds the identities and precise location of those buried in this section of cleared cemetery now at the centre of national attention, with some former students suggesting the majority of the 751 grave sites do not contain the remains of children from the residential school.

- Do you have information about residential schools? Email your tips to: WhereAreThey@cbc.ca.

Nevertheless, early Catholic mission records obtained by CBC News, along with the testimony of elders from the community who attended Marieval residential school, help shed some light on who could be buried there.

The records and testimony also suggest the Catholic Church has additional documents with some of the names connected to these unmarked graves.

‘Not a residential school grave site’: chief

Cowessess First Nation Chief Cadmus Delorme said that, according to local oral history, up to 75 per cent of the interred are children who attended Marieval residential school, which was run by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate.

“But I can’t confirm that,” he said in an interview with CBC News.

The Cowessess discovery sent shock waves across a country still reeling from the findings revealed three weeks earlier of another ground survey that identified 200 potential unmarked graves in an old apple orchard near a former residential school in Kamloops, B.C.

Other First Nations have since announced discoveries of unmarked graves, and searches at residential school sites across the country are ongoing.

In Cowessess, the announcement surfaced painful memories for survivors who attended Marieval residential school.

From the beginning, Delorme has maintained that the area surveyed also held remains of others from the community and surrounding region who did not attend the school.

“This is a Roman Catholic grave site. It’s not a residential school grave site,” he told CBC News.

“Other Roman Catholic faith-goers, Indigenous and not, adults as well, have been buried there…. There are one-metre-apart graves. We understand that those are not adult sizes.”

‘We’ve always known these were here’

Cowessess First Nation sits in Treaty 4 territory, along the deepest part of the Qu’Appelle Valley. Before the Catholic missionaries arrived and built the church and school in the late 1800s, the people from here buried their dead throughout the high, green hills that frame this Saulteaux and Cree community, said Lerat.

From Lerat’s home, taking a right turn before the Cowessess gas station and grocery store, then a left onto Oblates Road, sits the location of the old Catholic mission — the church and rectory now gone, burned in 2018 under suspicious circumstances.

This is where the oldest part of the cemetery begins. It is now a sea of little flags and small, solar-powered lights. There is also a headstone for a nun and a worn grave monument for three members of a German family from Grayson, Sask., a village about 25 kilometres north of Cowessess.

“We’ve always known these were there,” said Lerat of the unmarked graves.

He said the idea that the graves were primarily of children who attended the school took on a life of its own.

“It’s just the fact that the media picked up on unmarked graves, and the story actually created itself from there because that’s how it happens,” Lerat said.

The newer section of the cemetery is dotted with headstones and grave markers. A community member was recently buried there.

More consultation needed, some community members say

Some in Cowessess say they feel uneasy that the dark reality of residential schools, and the thousands of Indigenous children who never came home from them, has been blurred with the history of a cemetery where the wider community’s ancestors lie.

Linda Whiteman, 80, attended Marieval residential school along with her sister, Pearl Lerat, 78, from the late 1940s to the mid-1950s.

Whiteman said it hurt to hear news of the 751 unmarked graves from her community ricocheting across the country, because she thinks most of them do not contain the remains of children from the residential school.

“The older ones knew that it wasn’t all children in there,” she said. “I stayed home for two days straight because I didn’t want to go anywhere.

“It was very upsetting, to say the least. And it went national just about right away, overnight. But I hope that something good will come out of it, and people will learn the truth about it.”

Pearl Lerat said the sisters’ parents, grandparents and great-grandparents are buried there along with others from outside the First Nation.

“There was a mixture of everyone in that graveyard, in that cemetery,” she said.

“It was the surrounding farmers, and the beaches, you know, and on the north side of the river, there was a Métis community, and they had people buried as well in our cemetery.”

Lerat said she wished there would have been more consultation with the older generation before the Cowessess leadership held a news conference and announced the find.

WATCH | More unmarked graves found near former Sask., residential school:

WARNING: This story contains distressing details. Saskatchewan’s Cowessess First Nation says ground-penetrating radar recently found 751 unmarked graves near the former Marieval Residential School, but some answers about who might be buried there and what happened to the headstones can be found in the community’s oral history and some church documents. 7:00

“Ask for their advice, ask them the history that they remember. We were there. We lived it. We should know,” said Lerat.

“I’m not claiming to be 110 years old, to know everything, but I think I’ve experienced enough on my home reserve to remember not only the bad times but the good times.”

Mission records reveal hundreds of burials

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation recorded eight student deaths at Marieval from its opening in 1898 to its closing in 1997. The institution was taken over by the federal government in 1968 and then the First Nation in 1987.

Many federal Indian Affairs records were destroyed over the years, leaving gaps in the history of residential schools. The loss of those records makes it difficult to determine the exact number of children who died in the care of church and state.

- Lost Children

Two volumes of Indian Affairs funeral records from Cowessess First Nation, also known as Crooked Lake, were destroyed by the federal government between 1936 and 1956, according to archived files listing destroyed documents provided to CBC News by a researcher. These records may have provided additional information to what is held by the Catholic Church.

While Lloyd Lerat was a student, he said, he remembers one girl from the community dying at the school from illness.

“She got sick there and died in the residence,” he said.

“And her parents just lived down the valley.”

Early mission records obtained by CBC News through an online genealogy site maintained by the Mormon Church reveal that dozens of children were buried at the cemetery while it was overseen by the Oblates, but it’s not clear how many were from the residential school.

The records include an index for Volume 1 of the mission register, covering baptisms, marriages and burials from 1885 to 1933, along with several pages of handwritten entries.

The documents record about 450 burials during the 48-year period. CBC News was able to determine the ages in 184 of the recorded burials up to 1908. More than half are preschool-aged children or those who died at birth.

The rest range in age from six to 100. At least two school-aged children were buried after the residential school opened in 1898.

There are a total of four volumes of the mission register, with one held by the band and the rest by the Catholic Church, said Lloyd Lerat.

A band member fought to keep the four volumes in the community when the Oblates handed over operation of the residential school to the federal government in the late 1960s, said Lerat.

“She said those were the property of Cowessess, and they should stay here because these are our records,” said Lerat.

“She fought quite hard to keep them, but then she was threatened by the priest … that they would charge her with theft.”

The Archdiocese of Regina would not comment on whether any of the records CBC News obtained matched or added to documents in its possession.

In a statement, it said it is currently working with Cowessess First Nation, and any records related to the mission and the residential school would only be shared directly with the community.

The Archdiocese also asked CBC News to stop phoning the parish priest in Grayson — or any parish — in the search for additional records.

The parish in Grayson provided ministerial support to the church in Cowessess First Nation and CBC News was seeking access to the parish records in case they held any clues as to why a priest removed headstones in the early 1960s.

Cemetery was in ‘terrible shape’

The Archdiocese said it did not have any information on the removal of headstones.

Several stories have circulated for years on why the priest removed the grave markers.

In one version, the priest removed headstones in a dispute with the band leadership. In another version, horses damaged the gravestones and crosses one winter, and planned repairs never happened.

- Do you have information about unmarked graves, children who never came home or residential school staff and operations? Email your tips to WhereAreThey@cbc.ca.

Lerat heard a different story. He said the cemetery was in disrepair and the priest wanted it fixed up.

“The priest at that time basically informed all the parishioners, and people that had loved ones in there, that they better come and clean it up,” said Lerat.

“But not enough parishioners came out, apparently. So, he decided if you’re not going to look after it, this is how it’s going to be done.”

Ken Zimmer, 78, an amateur historian and retired headstone salesman, remembers walking through the cemetery in the mid-1950s. He said it was in “terrible shape” and some of the grave sites were sinking into the ground.

“A lot of monuments … were caved in, they were falling over, the grave covers were slanted in,” he said.

Later, bartending in nearby Grayson in the early 1960s, Zimmer heard from patrons that the priest removed the grave markers and plowed over the cemetery because human remains began to surface.

“[A] couple told me … that they visited, and they saw bones there. So, they kicked the bones in with their feet, they pushed the ground in on top to cover it up because they didn’t like to see that,” said Zimmer, whose research was used in a book about the region.

Zimmer said the couple told him they told the priest, who decided something had to be done, leading to the removal of all the markers, said Zimmer.

What lies outside cemetery boundaries?

The only evidence to surface to date that plots out the burial spots and names is in hand-drawn maps. A community member in charge of burials handed them down to his son, who took over the job until his death, said Lerat, and residents have since been circulating copies.

Pearl Lerat and Linda Whiteman showed CBC a copy of one such map covering burials from 1966 to 1989. Each grave was represented by a little square with a name and dates of birth and death. Several squares on the map were recorded as “unknown.”

“I think once they’re matched up along with the records that they receive from the church, then a lot of what they call the unmarked graves will be marked again,” said Lloyd Lerat.

What weighs on Lerat are the survey flags dotting areas outside the cemetery boundaries — the site of an old skating rink and where the church and rectory stood.

“What’s the shocking part is what’s out there? What we don’t know, what we didn’t know growing up, what we played over, you know, and treated as a schoolyard, but not knowing there were bodies there,” said Lerat.

“You would expect the church not to be part of the graveyard … What’s down there? We’re not sure.”

Support is available for anyone affected by their experience at residential schools and those who are triggered by these reports.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for residential school survivors and others affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419.