Going with the flow —

How a special design increased the efficiency of an ancient watermill.

Alice McBride

–

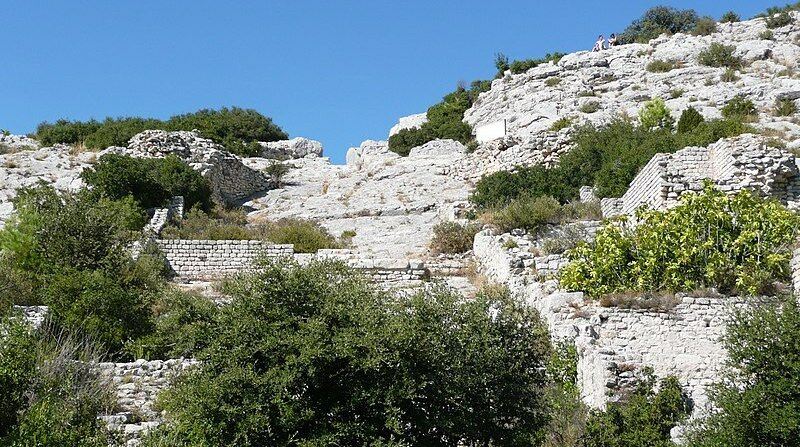

Enlarge / Given the present state of the watermills, reconstructing their operation wasn’t simple.

The Colosseum’s arches, the Pantheon’s dome, the Barbegal watermill’s… elbow flumes? Roman architecture is known for elegance and ingenuity. A curious relic, pieced together in a museum basement, shows that Roman design also boosted the efficiency of an ancient industrial complex built to function rather than impress.

The 2nd-century Barbegal watermill complex in southern France was no soaring monument meant to awe the masses. But neither was it a run-of-the-mill mill. It was the most formidable concentration of mechanical power known to have existed in ancient times—an array of 16 waterwheels, capable of grinding an estimated 55,000 pounds of flour on a daily basis.

Getting that array to work effectively required careful engineering thousands of years ago. And in the present day, with the mill complex in ruins, an international team of experts in archaeology, geology, and fluid mechanics was needed to piece together clues to the system of wooden chutes that channeled water efficiently through the complex. The key component the research team uncovered was an oddly shaped water gutter, unique in its design: the elbow flume.

Efficient engineering

Maximizing efficiency in the Barbegal mill complex would have been a tricky conundrum, because it was such an elaborate system. A series of aqueducts brought water from the closest river to the top of the hill into which the mill complex was built. The water then flowed over the waterwheels, which were arranged in two rows of eight running in parallel down the hillside. The waterwheels themselves were set into basins hewed from the rock.

“The mill complex is special,” said Cees Passchier. He’s a lead author on the study as well as a retired professor of structural geology and tectonics at the University of Mainz in Germany. “It is the only example we know of a Roman multi-mill complex. Normally you only find small mills.”

An ordinary mill has a single reservoir. Water from the reservoir runs via a flume to a waterwheel downstream. It’s easy to manipulate the water depth in the reservoir with a dam and a sluice gate. This means the flow of water is already under fine-tuned control before it enters the flume, and the flume itself can be a simple, straight gutter that directs water toward the wheel.

But the multitiered Barbegal complex didn’t have a single reservoir. Instead, it had those rows of carved-out basins set in a line running downhill. The basins served a dual purpose: catching the water that fell from one wheel, and simultaneously acting as the source of water for the next wheel in the series. Compared to a single reservoir, the water depth in these basins was harder to control. Passchier and his colleagues think the carefully shaped elbow flume—a roughly seven-foot-long gutter bent up at one end like the tip of a hockey stick—was designed to address this unique challenge.

“No such shapes are known from modern mills or from medieval mills,” Passchier said.

Reconstructing the mill

It almost wasn’t known from the Barbegal mills, either. Of the entire industrial complex, only a skeleton remains. The wooden waterwheels and other pieces of machinery have long since rotted away, leaving the inner workings of the Barbegal mills largely a mystery. But clues to the system remain because the mineral-rich water of the area left something behind: calcium carbonate, an old ally of archaeologists.

“Even though the wood itself was gone, because being organic it was all deteriorated, the mineral deposits—being a hard ceramic, essentially—remained,” said John Lambropoulos, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Rochester, who was not involved in the research.

Enlarge / The Barbegal mill complex was an industrial complex for food production.

Over the years, these carbonate deposits had become a stone-like layer built up in the rock basins and molded onto the wooden machinery. When the mill complex was first excavated in the 1930s, some of these carbonate deposits helped researchers make inferences about the internal machinery, like the dimensions and placement of the waterwheels. But many of the carbonate casts were just fragments, broken up in the intervening centuries. Fortunately, even these were saved—dutifully hauled away and stored in the archaeological museum in Arles, the closest city.

“For 80 years, these fragments had been there, somewhere in the giant basement of the museum,” Passchier said. Broken though they were, the carbonate fragments still held the key to the shapes of the wooden machinery they had formed on. Passchier and his colleagues cleaned and organized them. “We found that some fragments fitted together into this elbow shape. And it was clearly part of a water gutter.”

To understand where this strange gutter fit into the Barbegal mill complex, the research team looked at the patterns of the carbonate layers—which provide information about how the water flowed—and the dimensions of both the fragments and the mill complex itself. They modeled different possibilities, calculating how the water might have flowed through the mill, and concluded that the elbow-shaped flume had been used to direct water from the basin at the bottom of one waterwheel to the top of the next waterwheel down.

But with the fluctuating water depth of the mill complex’s multiple basins, just directing the water wasn’t enough—the flumes at Barbegal are needed to regulate the flow. The flumes had to be steep, so the water would reach a high speed as it dropped away from the basin, Passchier said. But they also had to be shallow, so the water would fall onto the wheel at the correct angle.

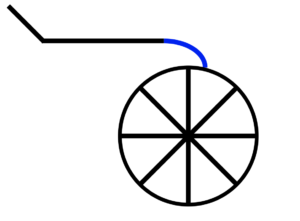

“You cannot have a steep and a shallow gutter at the same time—so the solution is to make the elbow.”

Giving it the elbow

A sharp drop near where the water exited the basin provided the acceleration for a rapid flow. The bend of the elbow then controlled that flow, the water moving nearly horizontally along the flume’s longer leg until it reached the next wheel.

Enlarge / The elbow flume accelerates the water quickly before bringing it over the water wheel through a long, flat stretch.

John Timmer

It was a simple, elegant answer to a complex design puzzle. According to Hubert Chanson, senior professor in hydraulic engineering at the University of Queensland in Australia, it suggests the ancient Romans had a better grasp of fluid mechanics and hydraulic engineering than has sometimes been assumed by scientists and historians.

“[Passchier and his colleagues] are basically proposing an idea that the Romans in fact had some understanding that they could improve their efficiency overall,” said Chanson, who reviewed an early draft of the elbow flume manuscript but was otherwise not involved in the research. “Whether it’s correct, who knows? But certainly it’s a very solid approach.”

In the modern day, the discovery of the elbow flume is unlikely to have much of an impact on current water management—technology has advanced well beyond the scope of the Barbegal mills in the past two millennia. But to Passchier, teasing out the lost workings of ancient technology is worthwhile nonetheless.

“[The elbow flume] is not going to change the way in which we see the world—but there could be other things in archaeology which can help us to find some cheap solutions to problems we have,” Passchier said. “What it shows is that, also in antiquity, people were creative. They had a problem, and they had to find a creative solution.”

Alice McBride is a writer and ecologist from Maine. She is currently pursuing a degree in science writing at MIT.

Listing image by Wikimedia Commons