In order to make room in crowded hospitals in the Greater Toronto Area, critical care paramedics with Ornge are transferring COVID patients to facilities in Kingston, London, St. Catharines, Barrie, Peterborough, Ottawa, Thunder Bay and Sudbury.

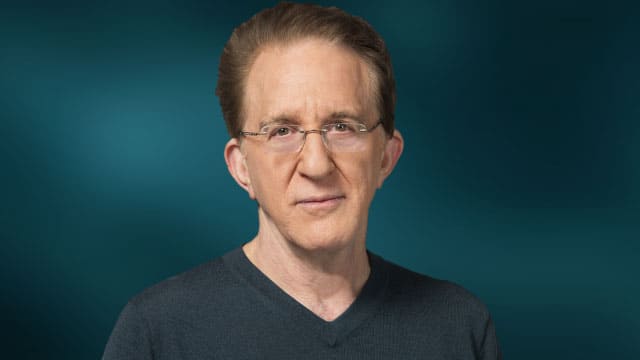

White Coat Black Art26:30A mobile ICU on the highway

When cases of COVID-19 surged as the pandemic’s third wave hit Ontario, Joanne Skinner told her 11-year-old son she’d soon need to go help people in Toronto.

A paramedic for 16 years, Skinner works for the Timmins, Ont., base of Ornge, the Ontario organization that provides medical transport by air and land to people who are critically ill or injured.

“I explained to him, ‘you know, there’s a lot of patients and a lot of moms and dads who are getting really, really sick,'” Skinner told White Coat, Black Art host Dr. Brian Goldman.

“He said, ‘Mom, I understand.'”

In order to make room in crowded hospitals in the Greater Toronto Area, paramedics like Skinner are transferring patients by land ambulance to facilities in Kingston, London, St. Catharines, Barrie, Peterborough, Ottawa, Thunder Bay and Sudbury.

In April alone, Ornge’s Emergency Operations Centre oversaw the transfer of more than 1,100 patients, Ornge officials say.

Skinner was also in Toronto to help out during the first wave, but the difference this time is striking, she told Goldman during an interview at Ornge’s Toronto headquarters where she was doing a seven-day stretch of 12-hour shifts.

“When we walk into Toronto hospitals, there’s usually ICU beds that might actually be empty. But now you’re looking and you’re seeing extremely sick patients and younger patients in each one of these ICU beds,” she said.

Skinner said she marvelled at the site of improvised rooms constructed out of plastic sheeting and hallways empty of visitors.

She and her colleagues routinely help with capacity at a busy hospital in the GTA’s devastated Peel Region. “And we pulled up to the hospital this week — I’ve never seen anything like it — there were ambulances lined up and down the side of the hospital. There were police cars. It looked like exactly what you see in a movie set during a pandemic, and it was, like, real life.”

Jostling patients

The procedures for transferring COVID patients are different than usual because of the infectious nature of their illness, she said.

Security staff escort paramedic teams down less busy hospital hallways to reduce the likelihood of the airborne illness passing to anyone else. The patient’s chart is condensed into one sheet of paper and read through a clear plastic bag to avoid contaminated paperwork.

The handover process — where the ICU nurse briefs paramedics on the patient’s condition — takes longer because COVID patients require numerous medications, said Skinner. And in most cases, the paramedics have a ventilator to monitor along the way.

“We also have to consider the fact that these roads are sometimes a challenge with bumping and jostling the patients around,” she said, noting they’re often travelling Ontario’s busy Highway 401.

“We have to make sure [their] seatbelts are very, very tight so that if we do hit that major bump, that they don’t end up moving off the stretcher a little bit, because sometimes a subtle movement can displace some of the tubes or even the IV lines.”

In normal circumstances, patients or their medical decision-makers have to agree to a transfer. But on April 9, the province’s health agency issued an emergency order that allows hospitals to transfer patients without their consent if those facilities are in danger of being overwhelmed.

That usually means taking patients to facilities further away from their families and primary care physicians, and “that definitely brings up some anxiety in some of our patients,” said Skinner.

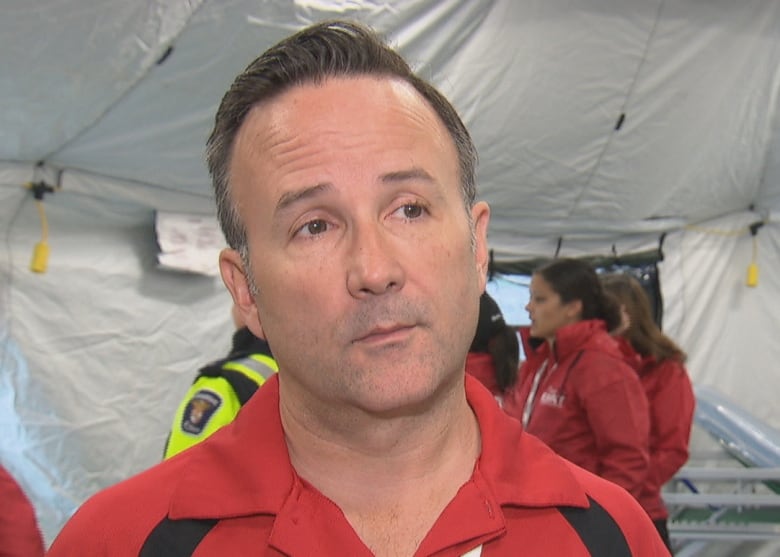

Dr. Chris Simpson, a cardiologist and executive vice-president at Ontario Health, said this situation came about because of how “asymmetrically” the pandemic has affected various regions within the province.

“The GTA has been very hard hit, and so if we hadn’t done the thousands of transfers from centre to centre, there would have been five or six or maybe even seven hospitals in the GTA that would have gone completely underwater — like completely overwhelmed — just from the sheer volume of really sick patients.”

If those steps hadn’t been taken, it would have meant “a Northern Italy scenario,” he said, where “you’d arrive in the emergency department in distress, needing intubation, [with] 20 others just like you in a packed emerg [ER] and an absolutely full ICU with nowhere to put anybody.”

We avoided the apocalypse. But we still have a disaster.– Dr. Chris Simpson, executive vice-president at Ontario Health

So far those transfers have meant hospitals haven’t had to use a triage tool established for a worst-case scenario where physicians have to decide who gets critical care because they can’t save everyone, said Simpson.

He said the redistribution of patients is “a success story inside a disaster.”

“We avoided the apocalypse. But we still have a disaster.”

Dr. Bruce Sawadsky, chief medical officer for Ornge, said although Ornge had pandemic planning in place that allowed it to scale up with more land ambulances, it’s the staff who have made it possible to increase capacity by 300 per cent.

“We only have about 200 critical care paramedics in the entire system, and so all of this has been on the backs of that small group of paramedics to step up and work the extra shifts, as well as our dispatch staff … who man the dispatch centre.”

Skinner said she’s able to remain positive in part because she’s never known a time when hospital staff and paramedics worked together better and with so much gratitude, “which has been actually a blessing.”

“If we could find some good in what’s coming out of COVID, I would definitely say it’s that patience and compassion and just being thankful for each other.”

Written by Brandie Weikle. Produced by Amina Zafar and Jeff Goodes.