Market forces —

Execs feel the strain as pandemic and government aid reduce supply and demand.

Aarian Marshall, wired.com

–

Unemployment in the US remains stubbornly high at 6.3 percent. Job growth has stalled, with 9.6 million fewer jobs in January than the same month a year earlier. But gig companies say they’re having trouble finding people to drive, pick up, and deliver for them.

“I’m worried about one thing going into the second half of the year: Are we going to have enough drivers to meet the demand that we’re going to have?” Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi told an analyst last month. DoorDash chief financial officer Prabir Adarkar called the situation “a tale of two cities,” with hordes of new customers racing to order takeout but fewer drivers offering to deliver it. DoorDash orders more than tripled in the last part of 2020, compared with the same period a year earlier.

The looming driver shortage confounds executives’ predictions. “With record unemployment, we expect driver supply to outstrip rider demand” for the “foreseeable future,” Lyft CEO Logan Green said in May. For a time early in the pandemic, Lyft blocked new drivers from signing up. It was understandable, because today’s tech gig companies were born during the Great Recession. They benefited from a deep pool of workers newly outfitted with smartphones and suddenly in need of supplemental income.

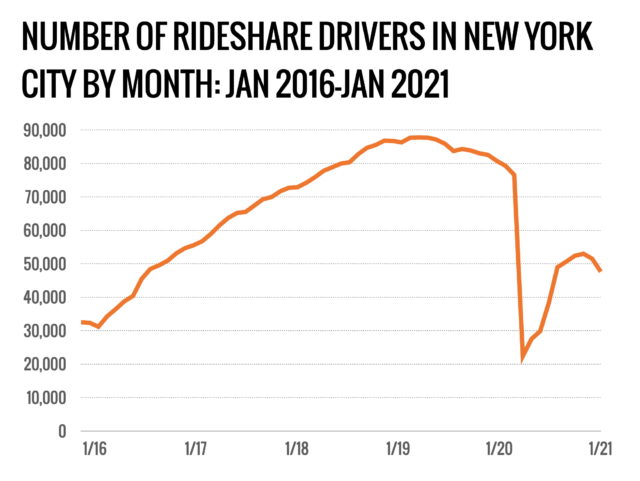

Enlarge / As business plunged during the pandemic, the number of drivers for app-based ride-hail services in New York City declined steeply.

Ars Technica; Data from New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission

Here’s why this time is different. After the pandemic hit, people stopped moving around, and demand for ride-hail went through the floor. Drivers responded by leaving the services. James Parrott, the director of economic and fiscal policies at The New School’s Center for New York City Affairs, has tracked the ebb and flow of ride-hail trips in New York City. His data suggests that the total number of rides in the city in January fell by roughly half compared with December 2019. The number of drivers fell too, to 47,600 from 82,500.

“The supply of drivers is not as good as it used to be, but demand for drivers is really not as good as it used to be,” says Paul Oyer, who studies economics at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He’s almost forgotten about Uber, he jokes. Like plenty of other Americans, he hasn’t been in one in months. Drivers, like so many others, have stopped working for health reasons: because they don’t want to catch the virus or because they live with people in high-risk categories.

The anxiety among executives about driver supply highlights a core feature of the gig economy and what the companies call their “two-sided marketplaces.” They have to balance demand for rides with supply. In fact, the companies rely on an oversupply of drivers, an army of independent workers standing by to respond to customer requests quickly, when and where they’re needed.

“One of the biggest challenges in ride-sharing is creating marketplace balance, making sure you have enough drivers for every rider,” Lyft’s Green said last month. “And the two respond on very different timelines.”

Caught in the net

Then there’s an unexpected factor: the nation’s hastily constructed pandemic safety net appears to be working, leaving people less desperate. Like most Americans, gig workers received stimulus checks—one last spring and a smaller one in January. (Another one appears to be on the way.) For gig workers who used to have other full-time jobs, states have extended unemployment insurance payments. And for the first time, gig workers—and all other freelancers—became eligible for a form of federal unemployment insurance, $600 a week.

Gig companies say they’ve felt the impact. A spokesperson for Uber says the company’s data suggests that its number of drivers available fluctuated according to unemployment insurance policies. When the stimulus hit drivers’ bank accounts, for example, fewer signed in to work on the app. Adarkar, the DoorDash CFO, told investors last month that “on the one hand, you would have expected a large influx of Dashers as a result of heightened unemployment. But that was offset to some degree by stimulus checks.”

Research from the JPMorgan Chase Institute published in 2018 suggests that families tend to turn to online gig work, especially driving, after someone in the household loses a job and needs to supplement their income. Basically, people sign on to gig when they need extra cash.

Newer research from the institute finds that the expansion of federal pandemic assistance and stimulus check programs have given families, especially low-income families, more cash on hand than they did before. By the end of the summer, average household bank accounts held 40 percent more money than they did the year before.

“I’m not surprised that people aren’t returning to platforms, because the government has done a really good job of meeting peoples’ needs,” says Fiona Greig, co-president of the institute. Pandemic assistance was designed to discourage workers from looking for jobs in the middle of a public health emergency. Unlike other state unemployment programs, it doesn’t demand that workers actively look for jobs while accepting payments. So for now, workers might not need to gig.

“Like steering and turning the Titanic”

According to executives’ comments, driver supply isn’t likely an existential issue, at least in the long term. It’s also pretty simple to solve. “As a labor economist—which I am—the market response for employers who have difficulty recruiting workers is to pay higher wages,” says the New School’s Parrott. There’s some anecdotal evidence that that’s happening: drivers in some cities—including Indianapolis, Oklahoma City, Pittsburgh, and Sacramento, California—say they’ve received emails and notifications from gig companies offering one-time bonuses if they sign on and complete a few trips. Lyft said last month that it would spend between $10 million and $20 million more this quarter on driver incentives, after cutting its recruitment costs by $15 million at the end of last year.

But the question of when to encourage workers to get behind the wheel is tricky. The companies want to have lots of people signed on and ready to go once more Americans get vaccinated and are ready to resume normalish lives, Uber rides included.

“Bringing more drivers onto the system takes time,” Green, the Lyft CEO, said last month. “It’s a little more like steering and turning the Titanic, whereas demand can move much faster.” Don’t tell him how that one ends.

This story originally appeared on wired.com.