All parents want the best for their children.

They want their children to be happy and to flourish. They want them to live out their dreams and reach their innate potential.

The challenge, however, is finding the right education model. One that doesn’t stifle their potential nor produce cookie-cutter pupils.

An excellent option to consider is positive education, which combines traditional education principles with research-backed ways of increasing happiness and wellbeing.

The fundamental goal of positive education is to promote flourishing or positive mental health within the school community.

(Norrish et al., 2013)

Continue exploring this article to learn more about the emerging field of positive education and how it is transforming lives around the world.

What Is Positive Education?

Positive education is the combination of traditional education principles with the study of happiness and wellbeing, using Martin Seligman‘s PERMA model and the Values in Action (VIA) classification.

Seligman, one of the founders of positive psychology, has incorporated positive psychology into education models as a way to decrease depression in younger people and enhance their wellbeing and happiness. By using his PERMA model (or its extension, the PERMAH framework) in schools, educators and practitioners aim to promote positive mental health among students and teachers.

The PERMA and PERMAH Frameworks

PERMA encompasses five main elements that Seligman premised as critical for long-term wellbeing:

- Positive Emotions: Feeling positive emotions such as joy, gratitude, interest, and hope;

- Engagement: Being fully absorbed in activities that use your skills but still challenge you;

- (Positive) Relationships: Having positive relationships;

- Meaning: Belonging to and serving something you believe is bigger than yourself;

- Accomplishment: Pursuing success, winning achievement, and mastery.

The PERMAH framework adds Health onto this, covering aspects such as sleep, exercise, and diet as part of a robust positive education program (Norrish & Seligman, 2015).

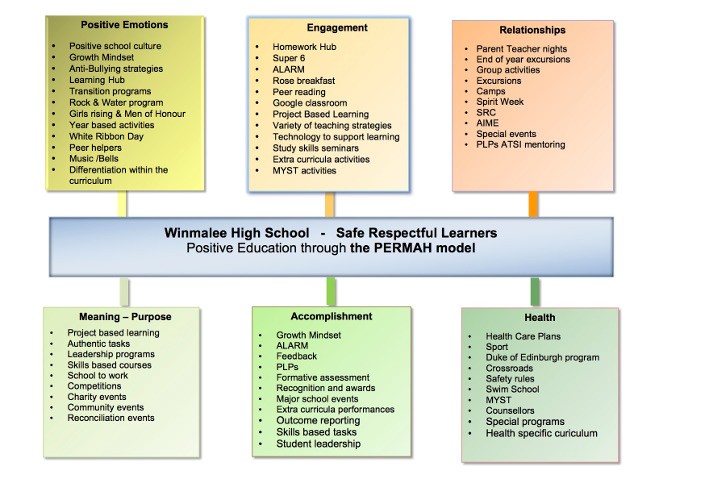

PERMAH in Practice

The figure below is provided by Winmalee High School in New South Wales, which shows how the PERMAH framework has been applied in practice through elements such as Project-Based Learning, Anti-Bullying Strategies, and more.

Source: Winmalee High School (2020)

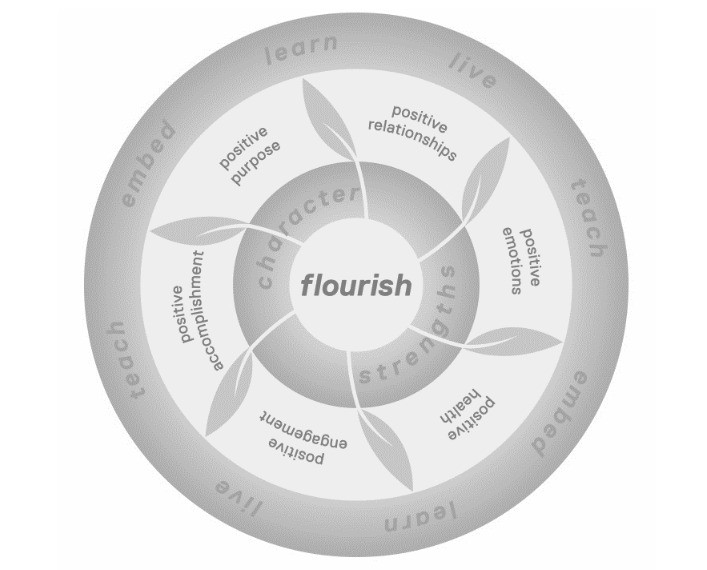

Below again, you’ll find another example from Geelong Grammar School, one of the earliest models in the field (Norrish et al., 2013)

Source: Norrish et al., (2013), in Hoare et al., (2017, p. 59)

VIA Character Strengths

Education has long focused on academics and fostering positive character strength development. However, before the publication of Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification by Peterson and Seligman (2014), any efforts to endorse character strengths were derived from religious, cultural, or political bias (Linkins et al., 2015).

The VIA classification, however, provides a cross-culturally relevant framework for ‘educating the heart’ (Linkins et al., 2015, p. 65).

Positive education programs usually define positive character using the core character strengths that are represented in the VIA classification’s six categories of virtue, which are:

- Wisdom and Knowledge;

- Courage;

- Humanity;

- Justice;

- Temperance;

- Transcendence.

These positive characters aren’t innate—they’re external constructs that need to be nurtured. The goal of positive education is to reveal a child’s combination of character strengths and to develop his or her ability to effectively engage those strengths (Linkins et al., 2015).

VIA Strengths In Practice

In practice, integrating character strengths into curricula can involve collecting information on students’ VIA strengths, talents, and interests when they enroll.

Revisiting these and communicating them to students throughout their academic journey can also be an excellent way to validate and nurture strengths, writes Geelong Grammar’s Institute of Positive Education Director Justin Robinson (2019).

How To Apply Positive Education

Strength-based interventions in educational systems are powerful tools that are often surprisingly simple to introduce into schools.

A school curriculum that incorporates wellbeing will ideally prevent depression, increase life satisfaction, encourage social responsibility, promote creativity, foster learning, and even enhance academic achievement (Waters, 2014).

The Geelong Grammar School (GGS) in Australia has often been cited as a model for positive education, since it was one of the first schools to apply positive psychology approaches schoolwide (Norrish & Seligman, 2015).

At GGS, all teachers and support staff participate in training programs to learn about positive education and how to apply its teachings in both their work and personal lives (Norrish & Seligman, 2015).

For students at the school, positive education is incorporated into every course. For example, in an art class, students might explore the concept of flourishing by creating a visual representation of the concept. The students also have regular lessons on positive psychology, just like they would with subjects like mathematics and geography (Norrish & Seligman, 2015).

These strength-based interventions also focus on the relationship between teachers and students. When a teacher gives feedback, they are instructed to be specific about the strength the student demonstrated rather than giving vague feedback like “Good job!”

Changes to these small interactions are significant, and paying attention to the wording of positive reinforcement has been shown to make a difference (The Langley Group, 2014). A study of praise conducted by Elizabeth Hurlock found it a more effective classroom motivator than punishment regardless of age, gender, or ability.

The following video summarizes the innovative ways schools are incorporating positive education into their curriculum.

The Art of Happiness Through Positive Education – Learning World

In Australia, one school focuses on wellbeing, under the belief that humans learn best when they are happy. The video above explains the application of positive psychology into the school system at Geelong Grammar.

Positive Education In Practice

The tenets of positive psychology have been used to create several teaching techniques proven to be effective in several ways. Here are just a sample of some ways to incorporate this model into any classroom or school system.

The tenets of positive psychology have been used to create several teaching techniques proven to be effective in several ways. Here are just a sample of some ways to incorporate this model into any classroom or school system.

The Jigsaw Classroom

One of these is the jigsaw classroom, a technique in which students are split into groups based on shared skills and competencies. Each student is assigned a different topic and told to find students from other groups who were given the same topic. The result is that each group has a set of students with different strengths, collaborating to research the same topic.

The influence of positive psychology has even extended to classroom dynamics. In positive psychology-influenced curricula, more power is given to the students in choosing their curriculum, and students are given responsibility from a much younger age. In these types of classroom settings, students are treated differently when it comes to praise and discipline.

The Character Growth Card

In 2013, Canadian-American journalist Paul Tough wrote a book called How Children Succeed, in which he argued that possessing inborn intelligence and academic competency is not enough for students to succeed in school. Instead, he argued that grit, resilience, and other character traits should receive a greater emphasis in schools. Doing so leads to better near-term academic performance in students.

The acclaimed charter school network KIPP took many of these ideas and made them an official part of school protocol. Students at KIPP schools receive a Character Growth Card, which evaluates students’ performance not just for academic subjects like math and history, but also regarding a series of seven character traits. These traits are culled from positive psychology research by Seligman and psychologist Chris Peterson.

KIPP’s system enables the formal assessment of traits that fall outside the metrics used to assess students at most schools, and it teaches the importance of these character traits in a few ways. Teachers model positive behavior, call out positive examples of the character traits in action, and discuss the traits openly and explicitly.

There are no formal lessons teaching character traits like zest or gratitude. Still, KIPP faculty believe that highlighting examples of these traits when they naturally occur is an effective way to encourage their development.

Not everyone seems to believe that KIPP’s method is effective. In an article in the New Republic, education professor Jeffrey Snyder argues that we don’t actually know how to teach character strengths, so numerically measuring them can do more harm than good.

Even critics of KIPP agree that calling attention to character and positive psychology in schools is a step in the right direction.

The Bounce Back Program and Building Resilience

In 2003, researchers Toni Noble and Helen McGrath devised a practical, cost-effective, and efficient classroom resiliency program called Bounce Back, the first positive education program in the world.

Noble and McGrath argue that teaching resilience to young children is most useful for lasting change, but that the most pressing need for increased resilience is during students’ transition into secondary school.

The Bounce Back program is targeted to upper primary and lower secondary students since adolescence is a critical period of change and stress for students.

Resilience: Bounce Back

Bounce Back addresses two key areas: the environmental factors that build up psychological capital and the personal coping skills that the students can learn, the importance of which has been highlighted by many researchers such as Seligman (2007), Reivich and Shatte (2003), and Barbara Fredrickson (2009).

What Noble and McGrath did was to provide a series of practical, day-to-day school activities that helped students feel connected to their peers, school, and the community. Their research showed how schools could create a more supportive environment, both within the school and in students’ families and communities.

To help students develop coping skills, the Bounce Back curriculum provides resources and suggestions for teachers and exercises for pupils. The exercises are designed to encourage pupils to develop optimism in the classroom and growing an accepting and light-hearted attitude.

Bounce Back provides practical tools such as a Responsibility Pie Chart, which guides children to realize that all negative situations are a combination of three factors: their own behavior, the behavior of others, and random events.

Using the Responsibility Pie Chart to understand a specific negative event helps pupils learn what they can change and what they can’t, developing their senses of initiative and responsibility.

These principles have proven useful for other client groups. Participants in Possibility Place, a program for boosting resilience and confidence in the long-term unemployed, found the responsibility pie chart very useful in preventing people from berating themselves for things that were not their fault and learning to understand what they could do to resolve the situation.

Bounce Back is a wonderful example of how positive psychology research can be transmuted into tools to help people flourish.

More Case Studies

As positive education grows in popularity across the world, there are increasingly more global cases of its implementation at the whole-systems-level. Some great examples include (Seligman & Adler, 2018):

Israel’s Maytiv Positive Education Program, which starts in pre-schools and stretches up to the high school level. While positive psychologists still call for cautious interpretation of extant data, the Maytiv Program has shown some promising results. Results such as enhanced student self-efficacy, positive emotions, a feeling of school belongingness, and improvements in the quantity and quality of social peer ties (Shoshani & Steinmetz, 2014; Shoshani et al., 2016; Shoshani & Slone, 2017).

In the UAE, Dubai’s Knowledge and Human Development Authority (KHDA) partnered with the South Australian Department of Education to conduct the Dubai Student Wellbeing Census. Following this, some UAE schools have been established on positive education principles, including rigorous training of all educators and the introduction of dedicated departments such as one school’s “wellbeing department.”

In Mexico, a Jalisco Ministry of Education and UPenn partnership also resulted in randomized controlled studies at educational institutions, with promising results. Based on these outcomes, a wellbeing curriculum (Currículum de Bienestar) was developed and implemented with beneficial impacts on measures such as academic performance, student connectedness, perseverance, and engagement (Adler, 2016).

Restorative Practices

Positive education doesn’t just focus on the positive parts of education; it also improves upon how schools administer punishment.

In any given school year, tens of thousands of students are expelled from U.S. public schools – in the 2015-2016 academic year, for example, over 11 million instructional days were lost, according to the ACLU (Washburn, 2018). Many of these students will be forced to leave their school for an entire academic year, while some others will be barred from ever attending a public school in their state.

Considering how many days of school and learning are lost to expulsions and suspensions, some school administrators are starting to rethink those methods. Expulsions and suspensions can sometimes be necessary if a student’s behavior is compromising the safety or learning environment of his or her fellow students.

Many educators now think these disciplinary measures are unlikely to help children learn from their mistakes or prevent repeat behavior once the offending students are back in school. Some argue that these punishments further alienate these children physically and emotionally from their peers, only making them more likely to repeat harmful behavior (Noble & McGrath, 2008).

An alternative method, called restorative practices, is championed by some as an improvement upon the expulsion and suspension model (McCluskey et al., 2008). Restorative practice isn’t an entirely new concept—it’s based on the restorative justice model that has been championed by criminal justice reform advocates for years.

In this model, a meeting is held between the person who “offended” someone, the person directly affected by the offender, and the community entangled in this domino effect of actions. The Venn Diagram offers a visual as to how these parties intersect.

If a school disciplines a student, it’s usually because the student’s behavior had a specific effect on his or her environment. The idea behind restorative practices is to focus on that effect when pursuing disciplinary action.

Let’s take a look at an example:

Let’s say a student named Maria was talking too loudly during class, disrupting her peers’ ability to focus. In a traditional disciplinary setting, the teacher might ask Maria to stop talking or give her a time-out.

In restorative practice, the teacher would ask Maria why she was speaking out of turn, what effect she’s having on the students around her, and whether she thinks it’s fair for the other students to be on the receiving end of that behavior.

In a more extreme case, like a student provoking and participating in a fight, the restorative practice would be more formal. The child would participate in a meeting with other students and adult leaders in the school. Together, they would discuss what spurred the student to start the fight, how it affected the others involved, and what the student might do instead if he or she was in a similar situation in the future (Hendry, 2010).

The student might also be assigned activities or programs that would help prevent further fights. As discussed on restorative practice in Edweek, a California middle-schooler named Danny went through a similar process. In Danny’s case, his disciplinary requirements included “writing letters of apology, undergoing tutoring, and joining a school sports team.”

While precise recidivism rates vary based on location, the data on restorative practices show promising results.

Further Positive Education Research

“A central question of youth development is how to get adolescents’ fires lit, how to have them develop the complex of dispositions and skills needed to take charge of their lives.” (Larson, 2000)

Lots of studies have been done on positive education and its potential impacts. Here are some summaries of research findings on the benefits of positive education.

Promoting Human Development

Sheila M. Clonan and colleagues (2004) found that the incorporation of positive psychology in learning environments helped foster individual strengths. It encouraged the development of positive institutions, and it made students more successful.

Still, more research confirms these results, including studies establishing that positive education interventions had a more lasting impact on changing student behavior than other methods (Adler, 2016).

Teaching Students How to Make Themselves Happy

In another study, researchers followed students aged 14-15 who completed a 40-minute timetabled lesson on the skills of wellbeing every two weeks for two years (Green, 2015).

The results showed that the students were able to gain a full understanding of what factors helped them thrive and flourish. In practice, students are better equipped to improve their subjective wellbeing in the longer-term through greater control over their positive emotional experiences (Fredrickson, 2001; 2011).

Decreasing Depression

Positive psychology interventions that are used in positive education include identifying and developing strengths, cultivating gratitude, and visualizing best possible selves (Seligman et al., 2005; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2006; Liau et al., 2016).

A meta-analysis conducted by Sin and Lyubomirksy (2009) with 4,266 participants found that positive psychology interventions do increase happiness and decrease depressive symptoms significantly. Further evidence from randomized clinical trials indicates a similar impact from positive psychology interventions in children (Kwok et al., 2016).

Facilitating Academic Performance

Compared to unhappy students, happier students pay better attention, are more creative, and have greater levels of community involvement (Fisher, 2015). The emphasis on positive psychology interventions in education increases engagement, creates more curious students and helps develop an overall love of learning (Fisher, 2015).

Among some of the great examples of positive education’s impacts on academic performance, we recommend Angela Duckworth’s work on grit, and Shankland and Rosset’s (2017) study on the positive relationship between learner wellbeing and academic performance (Duckworth, 2007; Villavicencio & Bernardo, 2016; Akos & Kretchmar, 2017; Mason, 2018).

Offering Easier Systems for Teachers

Positive education benefits teachers, too. It makes it easier for teachers to engage with students and persist in the work they need to do master their academic material (Fisher, 2015).

It creates a school culture that is caring and trusting, prevents problem behavior, and recent research suggests that the better teacher-student relationships may have their own academic performance advantages, in turn (Košir & Tement, 2014).

Increasing Motivation Among Students

Positive education also offers a fresh model of pedagogy that emphasizes personalized motivation to promote learning (Seligman et al., 2009; ).

Research has shown that goals associated positively with optimism resulted in a highly motivated student (Fadlelmula, 2010). This study showed that motivation may be consistent and long-term if it is always paired with positive psychology interventions.

Boosting Resilience

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania developed the Penn Resiliency Program. Results from 19 controlled studies of the Penn Resiliency Program found that students in the program were more optimistic, resilient, and hopeful. Their scores on standardized tests increased by 11%, and they had less anxiety approaching exams (Brunwasser et al., 2009).

Limitations in Research

Since this article was initially published, we’ve seen more and more impressive publications on positive education.

Where many earlier studies on positive psychology focused primarily on adults such as college students, we’re now welcoming research on students as young as pre-schoolers.

There will always be calls for more research, so what’s next, specifically?

Seligman and Adler (2016) suggest the following in a recent UPenn publication on Positive Education:

- More evidence on the reality of the wellbeing improvements and academic achievement data we’ve seen thus far;

- Rigorous cost-benefit analyses on existing positive education programs, which take effect sizes and duration of reported results into account;

- More scientific rigor in general across the field, including cross-validating measures, less obtrusive and reactive measures, and more big data techniques; and

- Treatment fidelity measurement – assessing how closely educators are adhering to the manuals they are provided in positive education systems.

Overall, however, the research findings have been promising so far, and time will tell what the future holds for positive education, and interest in applying positive psychology interventions in schools is growing rapidly.

Where Are We Now?

In the time since Seligman established the basic tenets of positive psychology, it has been implemented worldwide in many ways. While the objective of giving students the tools to build meaningful relationships, feel good, become well-rounded, and bring positivity to everything that they do, is common among all positive education institutions, each has its own approach to doing so.

For example, Perth College (an Anglican school for girls in Western Australia) trains its staff in positive psychology and coaching and have full units on ethical issues and social justice.

Other schools utilize what is known as the Montessori method, which emphasizes student-led, project-based curriculum to enhance creativity and hands-on learning.

With the success of many of these approaches and no single dominant method, many organizations are starting to grow in an attempt to consolidate and organize the efforts among different schools.

The International Positive Education Network is one of several institutions attempting to figure out what is working and spread it through means such as conferences and even policy reform.

Research conducted over the last two decades has suggested that these sorts of initiatives lead to students growing up with higher levels of creativity, leadership skills, and emotional intelligence (Leventhal et al., 2015). Furthermore, they even lead to improved academic performance and significantly better mental health (Adler, 2016).

With the unprecedented levels of anxiety and depression in the world today, proactively raising children to handle these problems effectively may be the best antidote we can provide. And in case you missed it, we included some great international examples of PE in action above, in Positive Education in Practice.

11 Positive Education Books For Parents and Teachers

Prefer to read about how other institutions have embraced positive education? Or, want to discover some tactical approaches for teaching strengths?

- Positive Education: The Geelong Grammar School Journey – by J. Norrish & M. Seligman

- Building Positive Behavior Support Systems in Schools: Functional Behavioral Assessment – by D. Crone, L. Hawken, & R. Horner

- Teaching that changes lives: 12 mindset tools for igniting the love of learning – by M. Adams

- Positive Academic Leadership: How to stop putting out fires and start making a difference – by J. Buller

- Playful Learning: Develop Your Child’s Sense of Joy and Wonder – by M. Bruehl

- Activities for Teaching Positive Psychology: A Guide for Instructors – by J. Froh & A. Parks

- Building Resilience in Children and Teens: Giving Kids Roots and Wings – by K. Ginsburg & M. Jablow

- Making wellbeing practical: an effective guide to helping schools thrive – by L. McKenna

- Positive psychology in practice: Promoting human flourishing in work, health, education, and everyday life – by S. Joseph

- Celebrating strengths: Building strengths-based schools – by J. Eades

- Reshaping School Culture: Implementing a Strengths-Based Approach in Schools – by E. Rawana, K. Brownlee, M. Probizanski, H. Harris, & D. Baxter

A Take-Home Message

To encourage positive education in more schools, researchers argue that more practitioners should share their knowledge and experiences. Can you recommend any books, strategies, institutions, or resources to your fellow educators? Have you got a case study from your personal experience?

Or perhaps you’re a researcher who is studying the field – in that case, what’s brand new? What would you like to see more of in positive education curricula?

Let us know; we’d like to hear from you. Share your insights below in our comments section.

By Catherine Moore